Room 2 - Egyptian and Mesopotamian Art

EGYPTIAN ART

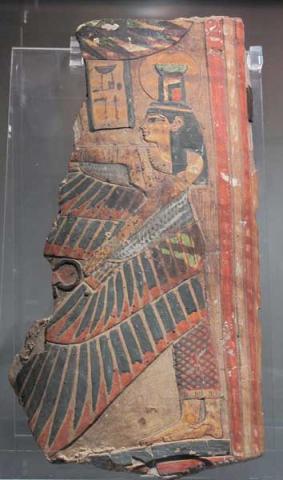

Sarcophagi

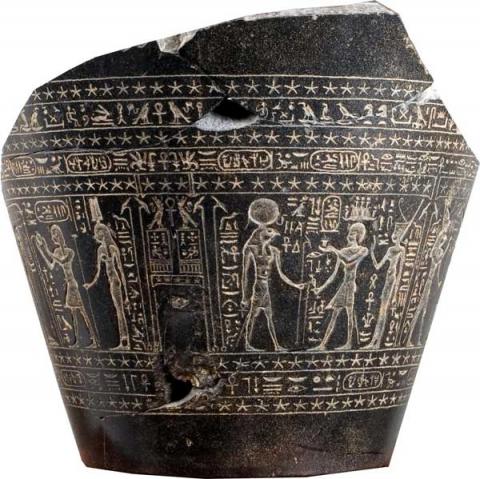

The ancient Egyptians usually defined the sarcophagus with the term “lord of life,” attributing to it the function of preserving the body so that it could pass through to the afterworld. In fact, the Egyptian religion believed that the Ka (the spirit) needed the body to survive after death.

The oldest type of Egyptian sarcophagus is a stone or wooden chest, variously decorated and sometimes bearing inscriptions. The other type we know of is in the shape of a human mummy. At first these were made of papier mâché: later on they were made of wood or stone.

Ushabtis

Ushabtis (the Egyptian word means ”those who answer”) are mummy-shaped figurines that were an integral and indispensable part of burial goods. They are holding farm tools (a hoe and a sickle). Inscribed on the front of each figurine is a chapter from the Book of the Dead. Reciting the inscriptions gave life to the figurines, which would thus work in the deceased’s stead. The Egyptians believed that after death the body reached the Iaru Fields, rich in fruit, crops and delights of all kinds. There it would live happily ever after, with no worries, enjoying the same standard of living as in earthly life, because the ushabtis would perform all the person’s tasks and provide for all the necessities of life in the afterworld.

Mummy masks

Masks, like sarcophaguses, played an important role in Egyptian funeral rites. They gave the deceased person a face in the afterworld and enabled the Ka (spirit) to recognize its body. The museum owns two of these masks.

MESOPOTAMIAN ART

Foundation nails

The name given to objects of this kind refers to the fact that they were buried at different points beneath the foundations of buildings, especially temples. Their primary purpose was to commemorate the building’s construction, but they also had an economic/administrative meaning that was transferred to the transcendent level. They were supposed to evoke the pickets used to measure fields and mark out building floor plans on the ground, and also the clay pickets inserted horizontally in the upper part of the walls. These clay pickets seem to derive from a prototype, the “secular picket,” that was driven into the ground to mark changes of ownership or property claims.

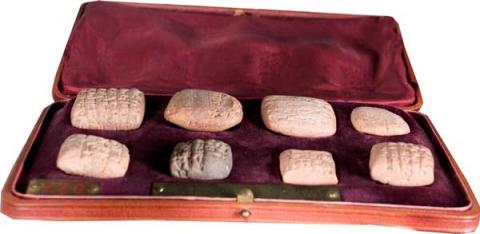

Cuneiform writing

The development of cuneiform writing is attributed to the Sumerian civilization, which flourished in lower Mesopotamia in the late fourth and the third millenniums B.C. Cuneiform was one of the first forms of writing documented in antiquity. It derives from an earlier and simpler writing system, known as pictographs, in which words were indicated by schematic drawings of the things they indicated. The term “cuneiform” (wedge-shaped) refers to the fact that the characters were written on clay tablets with a triangular-pointed reed stylus that produced wedge-shaped marks (cunei in Latin).

Parthian Art

This is the term used to denote the art which, between the third century B.C. and the third century A.D., was characteristic of the area extending from the Iranian highlands to southern Mesopotamia. Many of the works produced in that period have elements in the Hellenistic style, but are distinguished from the latter by a greater use of decoration.

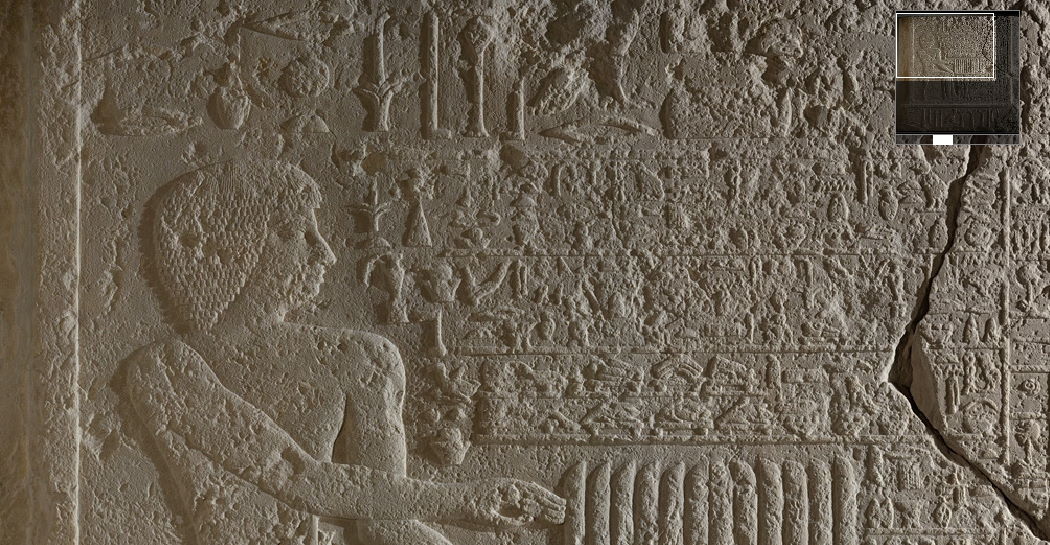

Assyrian reliefs

An important part of the collection is dedicated to Mesopotamian art and in particular to findings from the main buildings of the neo Assyrian kingdom. King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC), the first great ruler of Neo-Assyrian empire, established the new capital of the kingdom at Nimrud (whose ancient name was Kalkhu), where he built the great North-West Palace. From one of the rooms of the palace, decorated with mythical-symbolic subjects, comes the great relief with kneeling winged genius.

Sennacherib (704-681 BC) moved the capital of the kingdom to Nineveh. Here it was built the North Palace, also known as the “palace without a rival”, lavishly decorated with impressive wall decorations, celebrating the military takeover of the sovereign. Some fine reliefs with scenes of war and deportation of prisoners come from here.

Ashurbanipal (668-627 BC), whose reign saw the end of the neo-Assyrian empire, kept the capital at Nineveh, but he built a new palace: the North Palace. The building housed also the vast library the king had collected in all regions of Mesopotamia: more than 20,000 cuneiform tablets discovered in the English excavations of the XIX century (now in the British Museum) are the most precious cultural heritage left by the Mesopotamian civilization. From the North Palace come various numerous reliefs with scenes of hunting, war and deportation of prisoners.

Epoca tolemaica, Tolomeo el Filadelfo (285-246 a.J.C.)